My interview with Steven Moffat

|

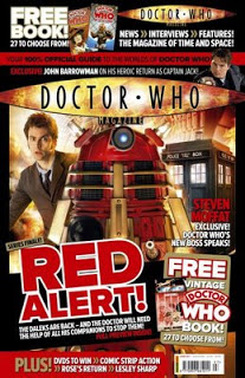

Because I love you, here's one of my favourite features I've written for Panini's Doctor Who Magazine. Originally published in issue 397 in June 2008, It comprises two separate interviews with Doctor Who showrunner Steven Moffat, both before he actually assumed that mantle. The first took place in September 2007, when he was a mere 20 pages into writing his 2008 two-parter Silence In The Library/Forest Of The Dead. The second was conducted six months later, when filming was in progress.

It's fun and instructive to chart Steven's thought processes as he constructs his latest Who tale and to see how things change along the way: sometimes because he changes his mind, sometimes because of production issues. He talks about River Song for the first time, too. But beyond all this, I think there's a great deal of insight into the swirling love-hate madness of being a writer and how much it extracts from you if you're doing it properly. There's also a load of good, general advice for writers. Enjoy... EPISODE ONE: THE POWER OF SECRETS Come with us, back through the time window. It’s September 6, 2007 and we’re settling down for a pint with Steven Moffat, outside a central London pub to avoid the hubbub within. It’s fair to say that he’s one of the most celebrated Doctor Who writers in history, as well as cutting swathes through British television by creating Press Gang and Coupling, then writing and executive-producing Jekyll. On a more global footing, he’s currently toiling over the Hollywood movie Tintin for little-known director Steven Spielberg. Oh, and he’s also the man destined to become Doctor Who’s showrunner in 2009. Not too shabby, then. We are a magazine with a mission: to follow the genesis of Steven’s latest Doctor Who scripts from start to finish, while simultaneously crawling inside his mind and having a good old root around. Right now, only 20 pages of the first script exist. Right now, we know nothing of Proper Dave’s glorious death, Donna’s face on a node, River Song’s death, her resurrection or any of the mad and truly wonderful ideas which will populate the finished episodes. But we imagine that it’s going to be rather good. Interestingly, after this first conversational episode, we still don’t know any details of Silence in the Library’s cliffhanger (“There’s an element of it that I can’t bear to tell you,” he teases, “I think one element of it will send prickles up the back of people’s necks”) or indeed the way in which the story will end. Not because Steven doesn’t know them, but because he doesn’t want to tell us yet. When we protest that this interview won’t be published until after the broadcast airs, his answer is one of the most illuminating things we’ve ever heard from a writer. But, tantalisingly, we’ll get there in a while. First, let’s recap on how Silence in the Library and Forest of the Dead came to be… “You think of an idea,” says Steven, on how his Doctor Who stories are born, “then think of all the things you’d like to do with it. “Ooh, it’d be creepy if that happened.” “Oh, my God, suppose the cliffhanger was like that!.” You can’t fit all these ideas into the story, but you have a lovely period - a golden honeymoon period - where you think you’ll be able to fit all of those in easily. Then you realise you can’t, and you start prioritising to all the cool bits.” Steven proposed the idea of “a big space-library” to showrunner Russell T Davies after handing in The Empty Child and The Doctor Dances for Series One. This library was set to have time windows: “connection points to all the libraries in the past,” as Steven puts it. “We were thinking about that for Series Two, but that’s when they were concerned about making historical episodes “funkier”. So they asked me to do the funked-up Madame du Pompadour story instead, which I did in the form of The Girl in the Fireplace. I couldn’t do time windows again after that story: it was a brilliant use of time windows and I didn’t think I could top it.” He pauses, then smirks, as he becomes aware of his self-congratulation. “Well it is!” he laughs. “Come on. He misses the girl he loves. That’s brilliant! Everything else is gonna seem weedy after that. And then, one idea I had for the monsters in the space-library were the Weeping Angels, but then I thought they didn’t really fit into the library world and so I put them into Blink.” When Russell came to assemble Series Three, he once again broached the space-library. However, the advent of Jekyll meant that Steven no longer had time to pen a two-parter and wrote the acclaimed Blink instead. If Steven has become known for a Doctor Who speciality, it’s perhaps the “puzzle box” story structure. Did Blink push that approach to the limit? “It probably did,” he says. “I don’t really know. I’m not sure what the limits are. As Russell says, it’s a new show every week. And you have to find it each time. It’s not like writing Coupling, Press Gang or any of those things, where you can get three or four pages in and it’s just actors having a bit of a chat! With Doctor Who you’ve got to get in there. Our pre-titles sequence now is the equivalent of the first episode of a four-part story on the old show. And in some ways, as much as I like that, I also miss the extended mystery of the old Part Ones. Those episodes were sometimes the best things about the story: that whole thing of “What’s going on this time?” But now that’s sorted within two minutes because we haven’t got bloody time: what’s the big idea and how fast can you get to it?” Steven Moffat’s key phrase while describing his new storyline is “very, very, very broadly...” “Um... At this point…” he begins, visibly working out how best to describe the concept. “First of all, we introduce the library like that!” He clicks his fingers and describes the first episode, stopping at River Song’s arrival. What can he tell us about her? “Very, very broadly,” he smiles, “She’s in her 40s, but will nevertheless be this story’s totty. Older totty! She will seem to know him and he will start to realise that she is one of his best friends, but he hasn’t met her yet and she is from his personal future. So that’s gonna be complicated. And throughout the story, we’ll cut between the adventures in the library and this little girl having nightmares about it. At one point, the Doctor tries to contact some kind of security system and rings the phone in her house: that kind of thing. So which of these worlds is real? Which is the dream? Of course, we’re likely to think that the Doctor’s world is real... but we’re going to challenge that.” As we push for more information, Steven clams up. “I am utterly incapable of giving away the ending to the story – you’ll have to accept this right now. I won’t even tell Russell – he’ll have to read it. Right now, he doesn’t even know the plot! He calls out “Spoilers!” if I tell him what I’m doing. I think it’s fair to say that he trusts me.” Interestingly, Steven does reveals what he calls “the most-likely-to-change thing: Donna ducks out of the library into the world of the little girl, living in a nice little town, then comes to believe that the Doctor was a dream.” Of course, this very event does, in fact, make it into Forest of the Dead. But shush – we don’t know that, right here, right now. Let’s not mess with the timestream. As for the monsters, Steven simply says, “Shadows. There are lines I’ve got written down for the Doctor, like, “What’s casting shadow?” And, “That’s not a shadow – it’s a swarm.” They’re sort of piranha shadows, which are really quite scary. Kids’ll never turn their lights off again, but that’s Doctor Who. It could be cracks in walls, or lumps under carpets. The whole thing is... there’s something else in your house!” Does Steven ever write early script drafts which hold back too much information? Which are just too darn mysterious? “It’s one of the most likely mistakes for me to make,” he nods. “The controlled release of information – which is more or less what storytelling is – is really, really hard. Especially on Doctor Who, where you do need quite a lot going on, because everything is new. It’s not like you’ve got a big regular cast, or one set that you’re going to see every week. In Doctor Who, you’re lucky if there’s one you see every week! So you need to release quite a lot of information. It’s a whole new world and you have to know what a normal day is like there, so you can twist it.” “I know that, in the past, Russell has given notes to writers, saying, “Tell everyone everything that’s going on, all of the time.” Broadly speaking, I wouldn’t agree with that to the last heartbeat, but I think that comes from the right place.” Your puzzle boxes are part of the light and shade of each series, though, right? Doctor Who doesn’t often serve up twists or big revelations, although Utopia is a noble and heavenly exception. “Absolutely. But that return of the Master feels set up, because it set up a long time ago with the Face of Boe’s death and message. So I think that, right up until the last minute, you’re constantly changing your mind about the release of information in a story. There’s a fine line between mysterious and confusing. And I’ve often drifted over it!” When you need feedback on a work-in-progress, who do you rely on for a fresh pair of eyes? “The Number One answer is absolutely Sue, my wife. Because, not only is she my wife, but we’ve worked together a lot.” Sue Vertue produced Steven’s sitcom Coupling across its four series. The first time the couple worked together was on Doctor Who: The Curse Of Fatal Death, 1999’s spoofy special for Comic Relief. “If I’m stuck on something, or confused,” says Steven, “Sue tends to be just about the only person who gets to read half my scripts.” Steven began writing Silence in the Library in order to establish a firm foundation, amid a whirl of projects. “When you have a lot of things to do,” he says, “sometimes it’s good to write a few pages so you then think, “Yes, I can do it”.” Can it be hard to recapture that mindset, though, when you return? “It can be, a little bit. In my whole writing career I’ve never juggled. I’ve always insisted on doing one thing at a time. This is the first time I’ve done several things at once. I’m finding it okay, but my mind does start wandering among them. I’ve had all three of the current scripts on the computer at the same time, and have at times moved a joke from one script to another!” Steven concedes that another reason for him wanting to write some pages was to “get my head around Donna, and how we can use her in the new series. It’s a very challenging, interesting thing and if we can bring it off it’ll be fantastic. But it’s harder work than bringing in a Rose, or a Sarah Jane, or a Martha.” Why’s that? “Because all the other companions are identical.” He sees DWM’s mock-shocked expression and laughs heartily. “They’re all the same person! You might change their hair colour, but... Jo Grant, Sarah Jane Smith, Rose Tyler... they all work terribly well. But they’re all quirky, feisty, dangerously attracted to dangerous older men. Principled and brave and absolutely marvellous. A lot of their life and colour comes from the performances. But oddly enough, if I was to make a comparison between an old companion and Donna, I’d say Leela. Leela’s different. Put Leela in the hands of a brilliant writer like Robert Holmes and you get that fantastic scene in The Talons of Weng-Chiang where she has dinner with Professor Lightfoot and he very politely agrees to eat with his hands too. That’s a gorgeous piece of observed comedy. Once the writing gets slacker, and it’s not Robert Holmes, it’s not so good. It’s harder work. You need to write a character like that well.” “Most companions tend not to get in the way of the plot,” he continues. “They’re absolutely trusting of the Doctor and absolutely capable of doing everything he asks them to do. When someone rebels, like Leela killing someone, or Donna not being as quite as good at all the companion stuff, you’ve got a bigger writing challenge. Like all bigger writing challenges, if you get it right it’s actually better. If you get it wrong [laughs], it probably won’t.” “So I was exchanging emails with Russell, talking about how to approach Donna. I’ve never done this before, but I said, “I’m gonna send you my first 20 pages I’ve written, so you can have a look.” And he sent some stuff he’d done, just to make sure we’re on the same page. It’s a bit of a mind-warp when you first think about it: Catherine Tate is Doctor Who’s companion and she’s older than the Doctor. But I just think, on Series Four, that’s gonna boost it. You can’t be lazy in any way. You can’t do any standard Doctor/companion riffs. At all.” Is there the danger of Donna becoming like mouthy, moany 80s companion Tegan Jovanka? “I actually liked Tegan, but the companion must love being there. Janet Fielding was a good actress and a sexy girl, but Tegan was constantly bloody complaining, which is a pain in the arse. You think, “What are you complaining about? These will be the days you remember for the rest of your life.” So I hate that. Whereas Donna is absolutely up for it and excited about the adventure, but she’s a bit more... human about it. I think that’s gonna be really interesting, and Catherine’s a fantastic actress.” Has Steven formed any theories, over the last three years, about how to structure the contemporary Doctor Who two-parter? “I think I have. The Empty Child and The Doctor Dances had a slight structural problem. Now obviously,” he laughs, “they went down rather well, so I’m not about to say they were terrible or anything! But there’s a point at which you get to the end of The Empty Child with the advancing gas mask people – and this goes for Aliens of London too, I think – and then the first 10 or 15 minutes of The Doctor Dances suffer a bit, because it’s a whole week later. Obviously it’s not a whole week later in the , but the Doctor’s still running around, away from the gas mask people. And you think, “Jesus, haven’t you moved on? Get over it!”.” “When it’s stuck together as a film, it makes perfect sense. But it’s movie-pacing more than two-parter pacing. So my new theory, which I will fail to live up to – and this will be pointed out endlessly until I die – is that there should be a turning point in the story at the end of Episode One that makes Episode Two a different kind of story. A revelation, twist, reversal or thought that changes the nature of the story. So it’s like, “Oh my goodness, the problem we’re dealing with now.” And when we start Episode Two you don’t feel, 'God they’re still running away from the gas mask people – they were doing that a week ago!'.” You mean, a curveball like the end of Part Four of 1978’s The Invasion of Time, when everything seems to have been sorted out, and the Sontarans suddenly appear? “Yes. I always thought that was a fantastic, fantastic cliffhanger. I never understood why anyone disliked that story. But I think Russell was on his second two-parter when he clocked what I’m clocking now. Which is, you can’t just carry on from where you left off, because it’s not a movie. The end of Bad Wolf was a fantastic cliffhanger, where the Doctor declares his intention to make war on the Daleks.” After a little prodding, Steven reveals why he’s passionate about keeping story elements, and especially endings, close to his chest before he actually writes them. “It changes the experience of writing it if I give too much away,” he says, simply. “Right now, I’ve got an idea for the ending which I’m extremely excited about, but I don’t wanna say it out loud. Not because it would matter if anyone knew about it, but just because saying it out loud might spoil the magic. You might look disappointed. So I need to cling to this idea. In fact, that’s a relevant thing to say about writing. Before, I’ve told people things and they seem underwhelmed, so I’ve lost faith in it from that point on!” It’s a remarkable revelation from a man who is largely seen as, shall we say, highly confident. But it makes you realise that all writers, of whatever stature, are prone to crippling self-doubt. More of which in Episode Two... “The most truthful thing I have said in this interview, about writing,” reckons Steven, “is the importance of these secrets. The magic of Not Telling Anyone Yet. I know Russell thinks that way too – he won’t tell anybody what he’s doing. Because it turns to ashes in your mouth. It almost becomes ordinary.” Over the next few months, Steven keeps in touch with us via e-mails which invariably contain the word “sorry”, as we try to arrange a follow-up interview. We schedule a second chat... exactly six months after the first. Due to recent events, we’re dying to remind him about something he said. Namely, this: “My estimate of how long a script should be is extremely good these days. With rare and apocalyptic exceptions, I’m pretty much on the money with running time. When I’m not, it’s pretty bad…” Cue Doctor Who’s cliffhanger screech and the closing credits... EPISODE TWO: ECHOES IN THE BAY

It’s March 6, 2008, and Steven Moffat has emerged unscathed from a pretty bad week. He’s sitting at the same pub table, with a different pint. Since we last sat here, he has written the Children In Need special Time Crash, which brought the Fifth and Tenth Doctors together. He has finished his Doctor Who scripts, which have been filmed. And... he has had to deliver extra scenes for Silence in the Library (formerly Series Four’s episode nine, but now episode eight), following the discovery that it had significantly under-run, clocking in at 37-ish minutes, as opposed to the standard 45. “It took us all by surprise,” he splutters. “And how long have we been working on this show? If something’s too long, all you’re gonna do is slowly improve the pace. It forces you to make critical decisions, and that’s good. But it’s the worst thing in the world to have a show like Doctor Who under-running, because it means you can’t alter or improve it. You’re just stuck with whatever’s there. In Series One, everything under-ran, so they used everything! But actually this episode is great. Really fabulous.” Steven can say this with confidence, having seen various edits of Silence in the Library. This week, he’s been embroiled in e-mail debates with production about the episode’s finer points. And we really finer. No hair has remained unsplit. “For instance,” he says, “There is a line, when River Song mentions the Vashta Nerada. It’s been mentioned before, but there’s no way that she could have heard the Doctor saying that – she was standing too far away. So I’m arguing that we should chuck River’s line, and Julie [Gardner]’s saying, “We think she’s heard it”. But even the audience will barely have made out what the Doctor said, and River’s saying it like she and the Doctor have had a little chat about the Vashta Nerada. She’s hip with the Vashta! And she shouldn’t be. But it’s a good line that leads to a good place, so we’re debating it.” And, as you’ll have seen by now, the line will be ditched. Reflecting back over the time since we last spoke, Steven recalls “a very busy end-of-year. I wrote the rest of the Silence in the Library episode in two or three weeks, which is quite quick for me. Then I did a third draft of Tintin – that was a real pound-at-the-typewriter affair, because the US Writer’s Strike was looming. I was literally writing past the midnight hour. And somewhere in that mess, I wrote Time Crash, while on holiday, in a couple of days. That was just ,” he grins. “Then I went back on to Doctor Who and the second episode. Not unreasonably, they wanted it in for the start of pre-production, which was November 19. I delivered it about a week after that deadline. I remember [director] Euros Lyn coming up to me and saying, “Sooooo... broadly speaking, what happens in the rest of this show?” I had to give him a list of all the things and settings, which were all in my head: the play-park, the under-library, special nodes... all that stuff. I only had 10 pages written but I knew what I was going to do.” “The first time a director reads a script,” he stresses, “it’s incredibly important to them. Because they need to recreate that story in the way they read it, in a way. And they need to come to it fresh, without me having said, “And there’s a twist at the end, with the sonic screwdriver.” Euros was extremely complimentary and excited about these episodes. But he’s the nicest man in the world, so he might well have been lying!” Steven adds that, when Russell finally read the scripts, “he was extremely enthusiastic.” But what would happen if you delivered a script that Russell had a major problem with? “Well, it hasn’t happened yet. But he’s the world’s best at dealing with that kind of scenario: he would find lovely things to say. At the same time, he is unrelentingly, almost shockingly honest. There is no comfort there – yes, he’s a lovely, big jolly man and genuinely delighted to see you, but he’ll just come out and say, “That doesn’t work.” He’s one of the most stingingly honest people you’ll ever meet. I think he’s just decided, obviously, that there simply isn’t time.” “Last time we spoke,” Steven confesses, “I wasn’t quite sure if the Donna cliffhanger was going to work, or what the logic was. I kind of worked out the logic afterwards! Having come up with the nodes, with the real faces – which was a creepy element – I just thought that the head of someone the Doctor loves had to end up on one of those nodes. When it’s Doctor Who, somehow you just have to do that!” “I don’t know how big a deal it’s gonna be now,” he considers. “The idea was always gonna be to cut to Donna’s head. It’s pretty chilling – and David does go for it a bit, with the Doctor floundering, in shock.” Did you add the threat of Proper Dave and co advancing, just in case the head didn’t have the impact you’d hoped? “Well, Donna’s head by itself wouldn’t quite send you into the cliffhanger. I’ve seen old Who cliffhangers attempting that sudden shock effect, but you need to build up to the right pitch with a bit of running about. But her face had to be the final image – which it wasn’t, in the first edit. It had to seem like Donna’s definitely dead – and mutilated! Because the other part of the cliffhanger is basically, “Is the Doctor under threat from slowly-advancing monsters?” The answer is pretty obvious, really!” Having expounded your theory about sending the second half of a two-parter spinning in a different direction, have you pulled it off? “I haven’t seen the second episode yet, but the first five or six minutes is Donna in her new world,” he nods. “And it’s like the story’s gone off somewhere else entirely! I think you need it. We’ll see a brief glimpse of the Doctor and co escaping, but if we stick with them capering around in the library again, it will seem like they’ve been capering around in the library for an awfully long time! My plan is, that hopefully by the time you come back to the library, you’re almost relieved that it still is Doctor Who!” Interestingly, you cited Donna’s New Life as the “most-likely-to-change thing.” What would have been the alternative? “Really?” he says, frowning. “I think I was to-ing and fro-ing at the time, because of the fact that Donna has another parallel existence in Turn Left. It’s only broadly similar, and it’s so completely different in terms of execution. But the reason this two-parter has been shunted back an episode to take it away from Turn Left, so that we don’t have two parallel worlds in a row. Still, all these months later, I’m surprised I would have said that, because it now seems so integral!” The presentation of Donna’s New Life is quite postmodern, in that the characters are only sentient within their scenes. Did you worry about going too far with such a bamboozling concept? “Well... I was going to do it as a more straight-forward series of rapid dissolves through Donna’s parallel life. But then I thought it’d be interesting if she was aware of the cuts – because we’re so used to that as a piece of television grammar. I think it’s rather cool: I like that. And I think I needed that, too, because otherwise there really might be people thinking, “ this Doctor Who? It seems to be a rather sweet little story about a lovely girl who meets a lovely bloke with a stammer.” So I thought we needed something that says, “Honestly, Doctor Who will be along in a minute. Itcoming back!” Did Steven decide to bring back River Song because he felt bad about killing her off? “No, I always wanted that. I wanted to do the really big, sad ending, then have the Doctor burst back through the door and save everybody. I sort of like big happy endings anyway. And it feels right – “Future Doctor” would’ve cheated. I had a line which I couldn’t quite fit in, where the Doctor said to Donna, “Why didn’t Future Me do something?”. And Donna was going to say, “But that’d be against all the rules of time”, then he’d say, “Exactly! Why didn’t he do it?” To me, it was inconceivable that, given that amount of time to think about it, Future Doctor wouldn’t set something up. I’d be quite keen on having the Doctor meet River again, but of course it’d be out of sequence – she wouldn’t have been to the library yet. And the Doctor would know a little bit of her future and she would know lots of his! He’d know where she’s going. But maybe he knows how his companions die – maybe he looks it up!” It’s remarkable how few of your Who stories feature actual death, isn’t it? “I literally haven’t had anybody die, except by natural causes. In six episodes, all the other deaths have been reversed! I suppose the characters in the library sort of die, but they have a nice afterlife. They’re all larking about in a huge library, reading!” So why the lack of actual death? Is it because of your love of the upbeat conclusion? “Well, The Girl in the Fireplace was all about mortality, and while Reinette dies from natural causes, that story’s about as sad an ending as I’ve ever written. It’s not so much the fact that she dies: it’s the fact that they missed each other. The Doctor made a tiny little mistake, and that was it. And Billy Shipton’s death in Blink is really a bit sad too.” He laughs. “Not killing anyone wasn’t a gameplan, and it can’t continue! I’ve really got to kill some people! But Doctor Who is a lovely, warm-hearted, optimistic show – I suppose I have difficulty in being really mean.” Understandable. And you still have plenty of demises which seem horrendous at the time. “Oh yeah. When Proper Dave’s skull bangs against his suit, that’s really, really nasty.” Proper Dave is a real highlight: was he always part of the story? “I had the idea for the skull and the animated suits, quite early on. It was a really great idea, to have a chicken leg eaten when it’s thrown into the shadows. But then, what are the shadows gonna – lurk unimpressively under a table [laughs]? They then need to do something else, so the stuff with the suits seems to ramp it up.” This two-parter sees another recurring Moffat motif: that of well-meaning automatons causing chaos. “If anything, it continues the idea that the villains aren’t necessarily evil. But I do think that straightforward evil is actually meaningless. All the evil acts in the history of the world have been committed with a pretty exact and precise agenda: people do what they think is right. You fly a plane into the World Trade Centre because you think it’s a necessary thing to do – not because you think it’s going to improve your day. It’s an insane and evil act – of course it is, it’s appalling – but it’s done to an . Real evil is just an agenda we don’t understand, and frequently we have to work out what it is. The Vashta Nerada just wake up and eat in their forest, which happens to have been transported to another planet. Why should they care?” Do you have a lurking fear of technology? “No, not really at all. I just think that Doctor Who stories work particularly well if there’s a good mystery: how does it all fit together? That’s good, because it puts the Doctor at the centre of the story. He’s going to be the man who decodes it, figures it out and pieces it together. If you just have villains who are evil and want to conquer the universe, what does that actually mean? Think what a lot of admin that would be! But if you have villains with complex ideas of their own, then the Doctor is again at the story’s centre. He works out what they want, and what it is that they’re trying to do. And stops it. But it allows him to have a big dramatic moment where he says, “This is what’s been going on,” and looks clever. Him looking clever is important. Whereas a straightforward military threat brings out the least interesting parts of the Doctor. He becomes a bit superfluous.” Is one of the few downsides of having misguided machines as the “villains” the fact that it robs you of a classic moral debate between the Doctor and his adversary? “Well, I mean... you can have the moral debate. But it’s slightly pointless because it then comes down to, “I’m better than you. I’m a good man and you’re a bad one!” It sort of works with the Daleks, but a lot of the time I’m not really sure I care about that. I care about the cleverness of the hero. So the more mystery there is in the story, the more there is for the Doctor to do. He is a kind of Sherlock Holmes character, who makes quick intuitive leaps and is absolutely brilliant.” These days, Steven does his best to adhere to a daily writing routine between 8.30am and 6.30pm, while a nanny looks after his children. “Back in the day, I probably lived a life not dissimilar to Russell’s: I went home and worked. My favourite time to write, back then, was from midnight ‘til five. I liked those quiet hours when no-one else is awake, and no-one else can bother you.” How do you stay focused? Sheer willpower? “You’re assuming I always stay focused,” he chuckles. “I don’t. No writer truly stays focused, all day, every day. Jesus it’s hard sometimes. Two or three hours will pass and I’ll have done nothing: not even had a useful thought!” What kind of thing distracts you... that you can talk about? He laughs hard. “God, the internet! Uh... but even if I deprive myself of all distractions, it really isn’t about that. You can go into an empty room with just a desk and a computer without internet, and you’d still lose focus. Because sometimes you’re not ready to write it. You’re not comfortable with what you’re doing and you have to get there.” Are there times you don’t feel like writing at all? “Every single day of my life! There isn’t one single script when I’m not, at some point, sick-makingly terrified of my inability to write it. I mean, . It’s just hard! I asked Russell, “Do you ever wanna stick your head out the window and shout, “I don’t know what I’m doing!”? And he said, “Oh God, every day.” He then mentioned it several times, saying how Cardiff Bay was echoing to his cries! And every time I make a script work, it feels like luck. I don’t think that feeling ever goes away. It really is that hard, and that’s what it’s supposed to be like. The sheer amount of thinking you have to do, to make this work! When I read scripts that are bad, it’s often because they’re just lazy. The writer hasn’t thought things through in the way that I would. There was a quote from John Cleese, around the time he was ruling the world with Fawlty Towers: “If I’m any good at writing comedy, it’s because I know how hard it’s supposed to be.” And that’s it. It’s shockingly difficult and emotionally upsetting!” Does it come back to the power of secrets, and the way in which outside views can affect even the most self-assured scribe? “No-one is that self-assured when they’re writing, or that assured about they’re writing. There’s no experience worse than handing your script in, and waiting. One of the glories of Doctor Who is that a writer is in charge. When you hand your script in to Russell, he’ll get back to you within literally about four hours. Or, he’ll say, “I can’t read this until...”, so you . You’re not left dangling!” Steven Moffat is naturally loath to predict how Silence in the Library and Forest of the Dead will sit among his distinguished body of Doctor Who work. “Maybe this’ll be the first unpopular one! I must be due for one that people don’t like. But it’s a good story, with good surprises and it keeps you going ‘til the end. It’s really well shot, with a great cast and everything else. But that’s the the story. Then it has this weird afterlife. People see it on television and talk about it. By this time, you’re actually working on something else. You’re interested in how people react to it, and you’re aware of it, but it doesn’t feel like anymore. It feels like .” So you feel a little bit disconnected? “Well yes. Unless people hate it. If people hate it, then that’s just horrible, let’s be clear!” Come May 16 2008, with the show-runner news about to break, we can’t resist returning to Steven with two more Columbo-style questions. Russell has recently said that Steven persuaded him to resurrect Jenny at the end of The Doctor's Daughter. Was that because Steven wanted to have the option of bringing Jenny back, when he became showrunner? “Oh, Lordy, that's got so overstated,” he says. “Truth is, I jumped out of my chair when Jenny came back to life - total surprise, loved it! And then I heard the podcast and discovered it was my idea. I was about to deny the whole thing, but then I checked back through my emails, and yep, I said that. It was before the script was written - Russell mentioned the idea he was about to give Stephen [Greenhorn, writer], and I said she shouldn't die at the end, cos that's what everyone would be expecting. That's all it was, a chat among writers - I didn't make a pronouncement from the balcony of my new Showrunner Palace.” How does it feel to know that your views and philosophies on Doctor Who in this very feature will be tirelessly picked apart and analysed by fans from now until you take your post? “It feels like... nothing,” he shrugs. “Sorry, not got any feelings about that. I'm sitting here trying to have a feeling, and nothing's happening. See, I'm a bloke, I don't really understand all this 'feelings' nonsense. If it doesn't hurt or tickle it doesn't count. Incidentally, there isn't really a Showrunner Palace. Though I do have a cape and a magic sword...” Thanks to Doctor Who Magazine for their kind permission to turn this feature into pixels. If you still haven't had enough 2008 Moffat action, then I ran some bonus material which didn't make the magazine, largely on more specifically writing-based topics, on my old blog here. The above interview (c) Jason Arnopp and Doctor Who Magazine. Do not reproduce more than excerpts without permission. |